A thesis piece covering the people of the whaling industry that shaped Long Island.

At its height in 1847, the whaling industry of Long Island produced 672,971 barrels of whale oil from several different species of whale. The profits produced by it were used to build up the port towns of Sag Harbor, Greenport, and Cold Spring Harbor.

The whaling industry and the towns that grew and benefited from its business have a history that involves Native Americans, women, and African Americans that tell the tale of Long Island’s whaling industry.

In 1839, David Gardiner a historian of the time talks about the history of whaling on the island in “The Chronicles of Easthampton.” His writings are published in “The Corrector,” is based on public records, and published papers, with collaboration of fellow writers of the period. There the necessity for the established industry is explained.

“This enterprise with danger and amusement was then followed to much profit. The salary of the clergyman was paid in oil, and it was sent to Boston, to procure the necessary articles of West India produce, and European manufacture.”

To the English, the whale’s value was in its blubber which was harvested and boiled in large pots to produce oil. One particular species of whale along the shores of the island were “Right” whales, that got their name due to their ease in being hunted, each producing about 50 barrels of oil.

To Native Americans the most valuable parts of the whale were fins and tails. The Montauk or Montaukket and Shinnecock people roasted and used them for sacrifice. John Strong, a historian with plenty of work over many years focusing on the whaling practices on Long Island writes how Long Island’s Native American tribes may have adopted the whaling practices.

“The origins of shore whaling practices along the New England coast remain obscure, but it seems likely that the Indians adapted some of the techniques used by the Basque fishermen who hunted off the Atlantic coast in the sixteenth century. There is little documentation, but it is known that these Basques traded for furs with coastal Indians. Basque whalers establish base-camps along the shore, resulting in cultural exchange which played a role in the evolution of aboriginal whale hunting.”

The English’s necessity for whale oil and Native American knowledge quickly fostered a relationship between the two with the first. Official contracting with Native Americans began in 1668, although informal agreements were made prior. The relationship strengthened as the reliance on English-manufactured goods and agricultural products by the Natives grew. The reliance was a result of land alienation as there was less available hunting and planting territory since it was being turned into English farmsteads. The ecological disruption led to a decrease in deer population and changing hunting practices that depended on guns, and supply of shot and powder which could only be gotten through trade.

By 1672, soon after the first formal contracting the English companies fearing Natives would have too much bargaining power, limited crew payment under law to half the share of the whale oil. That half share would be split amongst the crew depending on skill, task, attendance and diligence. This payment was delayed until the end of the season and before then would be used as a line of credit. The credit would be used for goods from the same company, they signed a contract. Most products were worth market value, although one price-gouged item sold to Native Americans was alcohol. If no whales were caught, the whaling company owners were not required to pay their workers, leaving many in much debt. With some contracts bonding them to continue work for the company until the debt was paid created a cycle of constant labor for the industry.

There were Natives who resisted this exploitation. Strong writes “Papasequin, a leader of a Montauk faction, traveled to Rhode Island in 1669 to establish close ties with Ninigret, a Niantic sachem known to be host to encroaching English settlements. The plan was foiled by the East Hampton settlers, who quickly disarmed the Montauks and threw their support to Poniute, a Montauk who led an accommodationist faction.” After this defeat Papasequin moved from Montauk to his relatives at Shinnecock. Once there, from 1671 to 1674 he is one of 20 Native Americans coming together to try to start a whaling company. It’s unclear whether the company ever operated. It stopped being mentioned and many men of the group were once again employed to English companies in 1675.

Although many whalers ended the season in debt, Papasequin was an exception; ending his 1679 season without debt and signing for another season in 1680. The next record of Papasequin is 1685 where he, wishing his seven-year old son to be raised in an English family, negotiates him to be indentured for ten years beginning in 1688. This decision was made by many poor white families in order to educate their children and teach them a skill. A Native American contract, by contrast, did not include educating their children in reading, writing or any skill.

Papasequin is last mentioned in 1703, where he and 31 other Montauks sign a deed transferring their land to Easthampton settlers.

Whaling and the exploitive nature of the “whale design” which relied on Native labor continues with such intensity that the North Atlantic Right Whale population drops significantly. This leads to Eastern Long Island production of oil dropping from 2000 in 1687 to 600 in 1707. This scarcity in whales along the shore leads to deep-sea voyages that would last months. This type of whaling was not implemented until after the American Revolutionary War.

Ships sailed out of Sag Harbor between 1784 and 1809 to bring in product with a market value of $600,000 to $1 million in today’s dollars. Unfortunately, this growth was stalled by the War of 1812, the Embargo Act, and threats from British vessels. After this came the “Golden Age” of whaling.

By this point, the whaling design has changed as Native Americans continued to increase their leverage and continue to be a driving labor force for the industry. The industry they helped found was one of the most diverse industries at the time with fishermen of various backgrounds and nationalities working the decks of the ship.

African Americans, who had worked on whaling ships since before the Revolution, were increasing in numbers. By 1859 there were 2,900 working in the whaling industry.

One of the most noteworthy of which is Pyrrhus Concer of Sag Harbor. Born a slave on March 17, 1814, Concer was taken from his mother and sold to the Pelletreau family where he stayed until he became a free man. Although the date and way of his freedom is contested, lying between 1832 and 1835, he was 18 to 21 and years younger than when the “Gradual Emancipation Act” of New York Law would’ve freed him, at 28. How he acquired his freedom may have been through the humanity of the Pelletreau family or by purchasing it with funds earned on his whaling voyages starting in July 1832.

His most notable trip, a three-year excursion, sailed from Sag Harbor in November, 1843. During this voyage they returned 22 Japanese men to Yedo, modern-day Tokyo. At the time the government’s policy was to either refuse foreign ships or send them to Nagasaki.

At Takeshiba Pier, Tokyo, where the ship landed, now stands a tall ship mast and a monument dedicated to the event.

The ship eventually returned to Sag Harbor in 1846, ending the almost 3 year excursion. In the coming years Pyrrhus Concer caught a case of Gold fever and went to California on a short expedition before settling back in Southampton and starting his ferry business, which was located on the town’s Lake Agawam. There he would ferry customers across the lake and rent out rowboats. He amassed a small fortune of $5,000 that, upon his death, he donated to various charities the largest sum of $1,000 going to the First Presbyterian Church of Southampton.

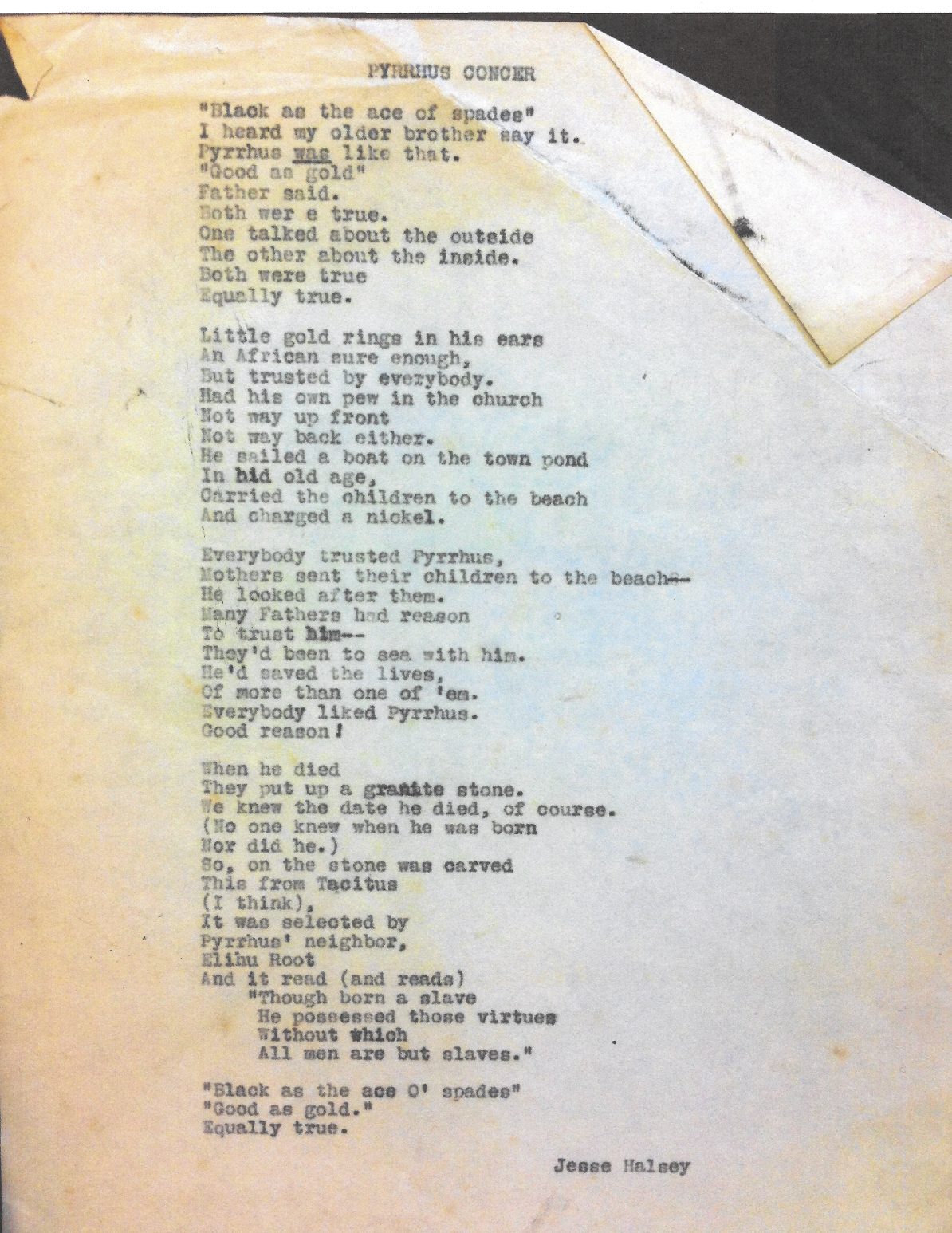

After his death, in 1897, Reverend Jesse Halsey writes a poem who’s first stanza begins

“‘Black as the ace of spades’

I heard my older brother say it.

Pyrrhus was like that.

‘Good as Gold’

Father said.

Both were true.”

The poem’s well intentions are subverted in one line in the second stanza

“An African sure enough,

But trusted by everybody.”

This line epitomizes the importance of Pyrrhus Concer, it shows that he is seen as an exception to the prejudiced views of Jim Crow Era America.

About the time Concer returned home in the mid 19th century, the whaling industry began to quickly decline with the growing scarcity of the whale and the discovery of petroleum in Pennsylvania.

Despite this decline, there was an increase in the number of women who chose to sail during this time, choosing to challenge gender norms of the maritime world.

Women would choose to sail the world and leave home in order to be closer to their husbands, usually captains of the ships, and maintain a family. Not every woman would go to sea, many would stay home and raise a family there, but those who did were breaking into male-dominated spheres.

The Sailing Circle, published by the Three Village Historical Society & Cold Spring Harbor Whaling Museum, reads:

“In 1872, the U.S. Census Office published the results of the ninth (1870) Federal population census, the first to provide a comprehensive listing of the female as well as male occupations. Of the 56,663 sailors tabulated, not a single one was female.”

Women who left their families and support networks found support in fellow “sister sailors” as they sailed the seas to the lands of Peru, Hong Kong, and Hawaii, all while bearing and rearing children.

“Capt. Henry Green’s wife is going to have a baby & she has gone north with him to have it on board the ship, for she says she isn’t a bit afraid to trust herself to her husband’s care,” Eliza Edwards of Sag Harbor writes of a fellow sister sailor “She has more confidence in him than I’d have in mine.”

When women were in a fleet, they’d gather for delivery but in order to avoid delivery on the ship entirely some would stay on land.

In October 1858 Eliza finds herself in Honolulu and writes to her family back on Long Island. “There is a captain’s wife boarding here by the name of Mrs. Childs… All last evening she concluded a little party and it resulted in a nice little girl baby weighing 7 lbs… myself and the doctor officiated. I expect you think I am getting initiated fast, but help is more difficult to obtain here than at home.” She sends an update to her later, “You know I wrote you about our little baby in the last letter, tis now 3 weeks old and both mother and babe are very well.”

Eliza’s letters also depict her exploration of the island, at one point going to a river with a fellow sister sailor. “I can’t describe it but Mrs. Palmer has seen Niagara & she said it looked just like the rapids there it was one solid mass of white foam lashing & dashing in every direction with all the fury you can imagine.”

The letters and diaries written by women on board include instances of helping injured men, illnesses suffered on the ship, taking over the job of terrible cooks, and occasionally saving their husbands from mutiny; all of which contributes to having a fuller understanding of what lives on whaling ships were.

Eventually, Eliza and her husband Eli Edwards would return to Sag Harbor in 1860 where she would live the rest of her life.

Today, after a bit more than a century, her words and that of her peers live on in the exhibit of The Whaling Museum & Education Center, Cold Spring Harbor. There, on a wall of an exhibit dedicated to the “sister sailors”, memorable quotes are written on one side of a block of wood, which when flipped around shows the author. This is thanks to the work of the museum’s staff of mostly women led by the director Nomi Dayan.

The effort done by today’s women to preserve the past doesn’t end there. Brenda Simmons, a member of the Pyrrhus Concer Action Committee, is working to rebuild Pyrrhus Concer’s home in Southampton, which was demolished in Spring of 2014. All that remains of the historic structure are some wooden beams, window panes and other pieces considered worth preserving some of which now have water damage due to mismanagement post demolition. The building, which was located in a historic district but lacked landmark status at the time, was bought in 2013 for $2.75 million by Brooklyn couple David Hermer and Silvia Campo in order to build a two-story home.

When the couple was denied permission for the demolition by the Southampton Village Architectural Review Board. They then filed a lawsuit of $10 million dollars against Southampton Town. This led to the demolition being approved on the condition that pieces of the home be saved.

Later that same year Hermer and Campo decided not to build their home but rather put the property up for sale. Southampton Town bought the property using $4.3 million of the Community Preservation Fund.

“I’m going to continue to fight until his homestead is built back up again” said Brenda Simmons

There is also work being done correcting the various social injustices caused by the exploitation of Native American land and labor. Earlier this year Cooperation Long Island released a document outlining a strategy for tackling issues of Indigenous sovereignty, education justice and restoration of tribal land rights. This land currently consists of the Shinnecock Hills Golf Course and Stony Brook Southampton campus, both of which would require federal legislation to be restored to the Shinnecock Nation.

History is written by the victors. The question now remains, who do we consider to be the victors? Those who made the industry possible by providing their labor or those who profited from the others by being at the top of a social hierarchy where systems were put in place to maintain their power?

- Long Island Historical Journal, Volume 02, Number 1

- Chronicles of Easthampton

- Southampton Record Books

- Southampton Magazine

- Indian Whalers On Long Island, 1669-1746

- Sag Harbor, The Story of an American Beauty

- Eliza T. Edwards Papers, 1857-1865, Coll. 248

- Disrupting the Narrative: Labor and Survivance for the Montauketts of Eastern Long Island

- A Family Affair: Whaling as Native American Household Strategy on Eastern Long Island, New York

- Indian Whalers On Long Island, 1669-1746

- Manhattan Log Book

- Documents relative to the colonial history of the state of New-York

- Pioneer American Merchants in Japan

- The Friend

- Sag Harbor Express